Thoughts on the question of whether robots will ‘take human jobs’

Written by Philip Graves, GWS Robotics, January 27th, 2017

The original text of this article has been selectively edited for ease of reading by David Graves, Creative Director of GWS Robotics.

It was further slightly edited for clarity by the original author on March 22nd, 2017.

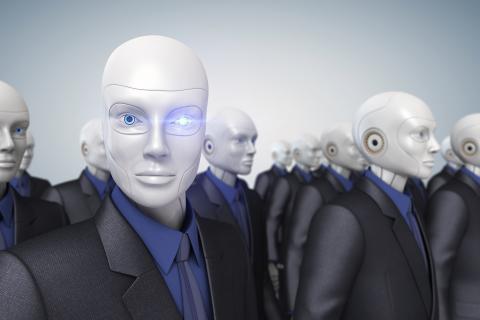

Are robots going to steal all our jobs?

There is something of a panic in some quarters about the risk of human jobs being taken by robots in the future.

So perhaps we should stop to consider what kinds of jobs may be at risk, and how economies have adapted previously to moves away from labour-intensive production processes.

In all areas of primary and secondary industry - from agriculture, mining, cable-laying and construction, to manufacturing, fabric-making and food processing – machinery for automated production and operations has been under continual development since the dawn of the industrial revolution in the 19th century. Over the past two centuries, its capabilities and efficiencies have improved in leaps and bounds. The number of worker-hours required to achieve a given level of productivity has markedly declined, at the same time as the total scale of industrial production and operations per person has enormously increased.

In the twentieth century, operational efficiencies and automation improved faster than demand for production increased, so there was a progressive decline in the proportion of the British workforce that needed to be employed in primary and secondary industries in order to meet all the production demands. Allied to the increasing globalisation of the industrial economy and the lower costs of production in poorer countries, this led to significant shedding of jobs in industrial sectors in the United Kingdom. But the jobs lost from these industries have been replaced with new ones in other sectors, chiefly in the service economy.

A certain level of unemployment is an almost universal feature of the modern, capital-intensive post-industrial economy. But another twentieth century trend, and one that is entirely to be lauded and welcomed by society as a move in the direction of greater economic fairness between the sexes (though inequalities remain to this day), has been the movement of most adult women into the labour market, as compared with only a minority at the beginning of the century. The national census of 1911 records that women accounted for only 29% of the British workforce at that time, with 5.85 million women ‘occupied’ as compared with 14.3 million men[1]. The rate of employment among married women in 1911 was just 10%.

The trend to fuller female employment has continued into the 21st century. The Office for National Statistics records that in the summer of 2016, economic inactivity among British women aged 16-64 had reached a record low of 26.8%, compared with 44.5% when records began in early 1971. This reduction in female working-age unemployment over the past 45 years has more than counterbalanced the moderate increase in male working-age unemployment over the same period (it rose from from 4.9% to 16.5%). So in 2016, the overall proportion of British working-age adults in paid employment was marginally higher than it had been back in 1971 despite advances in automation and reduced demand for labour in traditional industrial sectors.

This history shows that when advances in automation take away jobs in some areas, the labour economy is adaptable enough to rebalance itself in the medium-to-long term. New economic sectors that demand personnel open up. The service, leisure, travel and entertainment economies are among the areas that have benefitted from increasingly automated industrial processes. In terms of gross domestic product per head, the economy has grown with automation. And in terms of jobs, it has remained stable in the national and longer-term view despite regional and sector-level declines.

As more and more robots are used in industry, we can expect a continuation of these pre-existing trends. Robots will of course directly replace some existing jobs, but they will also free those parts of the workforce up to work in other areas, though this process may be painful. Money saved by automation in industry should find its way back into the economy as spending and investment power in other sectors, allowing them to employ more people.

It is also likely that some futurologists have been promoting an exaggerated picture of just how many of the jobs undertaken by humans today can satisfactorily and fully be replaced by robots in the next fifty years. From a customer service perspective, for instance, robots will chiefly be creating added value by providing additional information and entertainment, just as home computers and Internet services do today. They will not by themselves satisfy the keenly-felt human demand for service with a smile from a congenial real person.

Robots will always be most useful doing the most boring, repetitive, mechanical and dangerous jobs. We believe that deploying robots in these areas will be of real human benefit, freeing a great many employees from drudgery and unpleasant working conditions. When the economy rebalances in due course, it is likely that new jobs will be the result.

Robots will require development, programming, servicing and monitoring, all of which jobs have to be done by people. So each robot deployed will not in fact be replacing a whole person’s job, even before the economic rebalancing that occurs after jobs are lost in any particular industrial sector.

On a personal and local community level, job cuts and factory closures can of course be a great shock and a tragedy for people where they occur. Such changes seem to be an inevitable part of a modern economy run on competitive free-market principles, and in this respect, increased automation may have a similar effect to competition from companies based abroad. Both central and local government social policy should, however, be ready to step in to make sure that the needs of individuals and communities affected by loss of employment in particular industrial sectors are met. Investment in retraining schemes for individuals and economic regeneration programmes for urban areas that have suffered from the loss of major employers are among the tools that should be used to facilitate the process of adaptation to sectoral job losses as painlessly as possible.

How does the economy rebalance itself after sectoral job losses?

This further elucidation was written by Philip Graves of GWS Robotics on 31st January, 2017 in response to an enquiry

How do we demonstrate that jobs lost to machinery are eventually replaced with new ones in other sectors, mainly the service economy? Economies naturally self-balance in that way over time because of there being certain economic constants such as the total amount of spending power and labour time per head in the economy as a whole. These constants dictate that economic savings in one area translate into opportunities for expenditure in another.

So, if the advent of automated processes leads to 50% of jobs being lost in a particular industry, either the prices of that industry’s output will fall in line with the savings on labour costs, as a result of which the people who habitually buy that output will find they have more money left to make purchases of other things (e.g. services), or, if the prices stay the same, the money saved on production will, as profit, find its way back into the economy sooner or later in the form of expenditure by the owners, directors and shareholders, and (provided that fiscal policy is properly configured by central government) as tax. This saved money is then available sooner or later for the purchase of other products and services. What dictates the kinds of products and services that are bought when money is saved on the labour costs of industrial production will vary hugely according to the tastes and habits of the times, but the sectors where there is demand will be the ones that grow and create new jobs.

There is generally no simple and direct migration of jobs from one particular industry into another. But historically we have seen the services sector collectively being the main beneficiary of the decline of employment in traditional primary and secondary industries.

See for example the publication in June 2013 by the Office for National Statistics of the document ‘170 Years of Industrial Change across England and Wales’.

This states that in 1841, 36% of jobs were in manufacturing, 22% were in agriculture and fishing, and 33% in services, whereas by 2011, only 9% of jobs were in manufacturing, 1% were in agriculture and fishing, and 81% were in services.

In short, as food and industrial production becomes more efficient in terms of labour, there is more money to go round for expenditure on services, and as a result, demand for employment in service industries increases.

[1] Hogg, Sallie Heller ‘The Employment of Women in Great Britain 1891-1921’ (1967)